What happens when you want to land, but the wind isn’t directly down the runway?

Well, if you happen to be flying in the Navy you can radio to the ship captain to position the runway at a better angle.

For the rest of us, you have to make a crosswind landing.

Although this can be difficult for some student pilots to master, with enough practice they can become very manageable!

What is a crosswind landing?

A crosswind landing is when you land with the wind blowing across the runway perpendicularly.

A lot of airports will have multiple runways to try to limit the amount of crosswind you will be exposed to.

This isn’t always practical and you will eventually fly into an airport with a single runway.

Even if your airport has multiple runways, you may be flying a large enough airplane to be forced to make a crosswind landing anyways (due to weight restrictions or runway length requirements).

Related Article – Class G Airspace Explained

3 Crosswind landing techniques

The three crosswind landing techniques are the crab method, the sideslip (also know as the wing-low method) and the de-crab method (also known as the combination method).

The crab method allows that pilot easily track the centerline, but requires a great deal of skill just prior to touchdown.

The sideslip is easier than the crab method when it comes to touching down without any sideload, but requires holding the aircraft in uncoordinated flight.

The decrab method is simply a combination of the other two.

What is the side slip method?

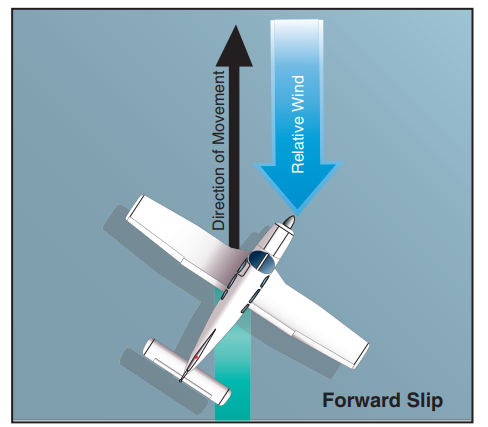

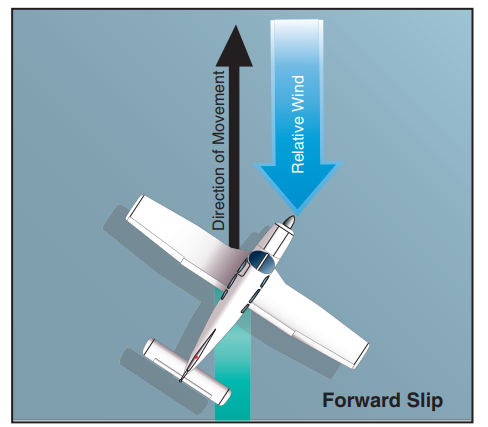

The side slip method of mitigating a crosswind involves lowering your upwind wing while counteracting any turning tendencies with opposite rudder.

We’re usually introduced to the words “slip and skid” when learning how to make coordinated turns.

A slip occurs when the ball of the turn coordinator (also known as the inclinometer) falls to the inside of the turn (not enough rudder for the amount of bank).

A skid is just the opposite and occurs when the ball moves to the outside of the turn (too much rudder for the amount of bank).

If the ball is centered we’re considered coordinated. In coordinated flight we do not feel like we are sliding in our seat and we know that the airplane has favorable stall characteristics.

After being conditioned to think of a slip in a negative context it can feel awkward to perform one intentionally.

Keep in mind that the goal of a crosswind landing is to be able to land so that the landing gear is not subjected to any sideload or cornering (the angular difference between the heading of a tire and its path).

Flying the sideslip method, although it feels awkward at first, will allow for a stabilized approach and a touchdown with no sideload.

What is the crab method?

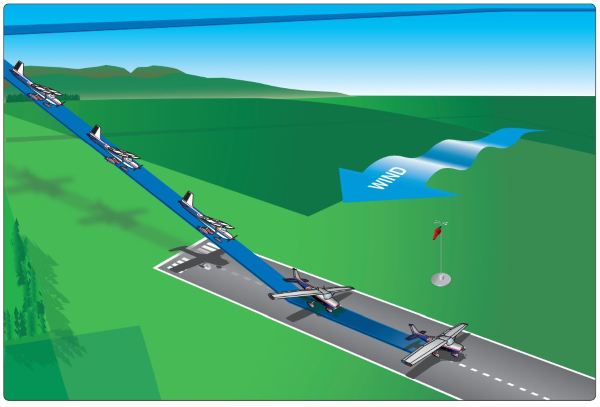

Performing the crab method involves keeping the airplane coordinated and turned into the wind.

The pilot establishes the proper heading into the wind so that the airplanes ground track remains centered on the runway.

The pilot will remove the crab during the flare to ensure that the airplanes wheels do not land with any side load.

Sideslip method explained

In order to perform the sideslip you will need to first determine which direction your crosswind is coming from.

You should already have an idea if you got the weather beforehand.

Once you’re at the airport you can easily determine your crosswind by looking at the windsock or by simply observing which way the wind is blowing you.

You want to prevent the wind from blowing you off course by lowering your upwind wing into the wind.

Lowering your wing will cause the airplane to want to turn. You do not want the airplane to turn and will need to combat this with opposite rudder.

Once you have put in just enough aileron to maintain centerline and enough rudder to keep the longitudinal axis of the plane lined up with the runway you’re all set.

After that you simply make minor adjustments as needed to maintain a stabilized approach.

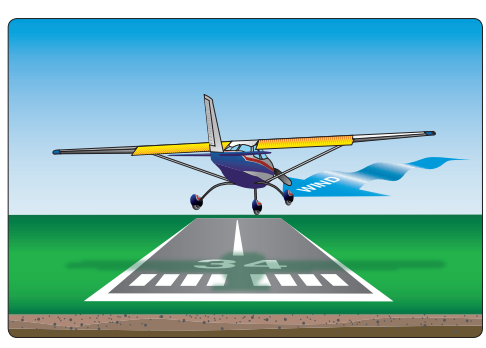

You will land on your upwind wheel first and as the airplane settles onto the ground you will fully deflect your ailerons into the wind. This will prevent the wind from getting under your wing.

Related Article – Choosing A Flight School Near You

Crab method explained

In order to crab the airplane in a crosswind landing you will need to determine what heading will keep your ground track moving forward.

You turn into the wind and use rudder to remain coordinated.

Once you have turned into the wind enough to prevent it from blowing you off course you hold that heading until it is time to flare.

Just prior to touchdown you need to quickly take out the correction so that you land without any sideload.

During the rollout you will “turn into the wind” with the ailerons and use coordinated rudder/nose steering to maintain directional control (the same way you would with the sideslip method).

What is the decrab method?

The decrab method is a combination of both.

It involves crabbing into the wind for the majority of your final approach so that you can avoid prolonged uncoordinated flight.

As you get to short final you transition to the wing low, sideslip method. This way you do not have to worry about timing the removal of the drift correction during the flare.

The decrab method gives you the best of both methods.

The rollout is completed the same way as the other two methods.

What is crosswind component?

The amount of crosswind you will be exposed to is referred to as the crosswind component.

Regardless of what method you use on your approach you will need your rudder to maintain longitudinal directional control against the wind.

At a certain point the wind is going to be too strong for your rudder. This is when the crosswind component has been exceeded and it becomes critical to go around and find an alternate airport with more favorable conditions.

How to determine crosswind component?

You obviously want to determine the expected crosswind component at your destination as part of your preflight planning.

In order to do this you will need to:

- Determine the surface wind forecast at the time of your arrival. The easiest method for doing this is through a TAF, if one exists. If a TAF does not exist you can use the surface winds chart from www.aviationweather.gov or www.1800wxbrief.com.

- Convert the winds in the TAF from true into magnetic

- Find the angular difference between the magnetic winds and the runway of intended use

- Refer to a crosswind chart

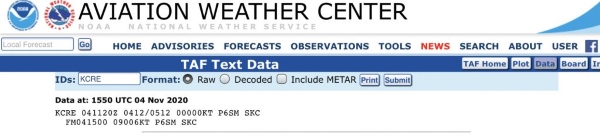

As a example, lets predict our crosswind for a landing at KCRE at 1600Z. Here is an example of a TAF:

We determine the wind for our ETA to be from 090 degrees true at 6 knots.

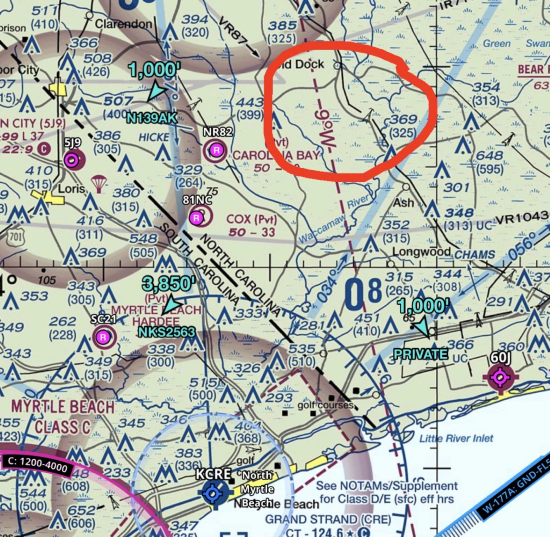

We then look at our sectional chart to determine how much variation we have at KCRE and determine we have about 9 degrees of westerly correction

We can now translate the TAF winds from True to Magnetic by adding 9 degrees.

Remember, we add westerly correction and subtract easterly correction. Think “East is least (subtraction) and west is best (addition)”

By adding the 9 degrees we arrive at winds 099 at 6 knots. We’ll round that up to 100 degrees for simplicity. KCRE has Runway 5-23 available.

100 degrees (wind) – 50 degrees (magnetic direction of RWY 5) = 50 degrees angular difference.

230 degrees (magnetic direction of RWY 23) – 100 degrees (wind) = 130 degrees angular difference.

We pick runway 5 since that has the least amount of angular difference. Now we can use a crosswind component chart to determine how much of a crosswind component we have:

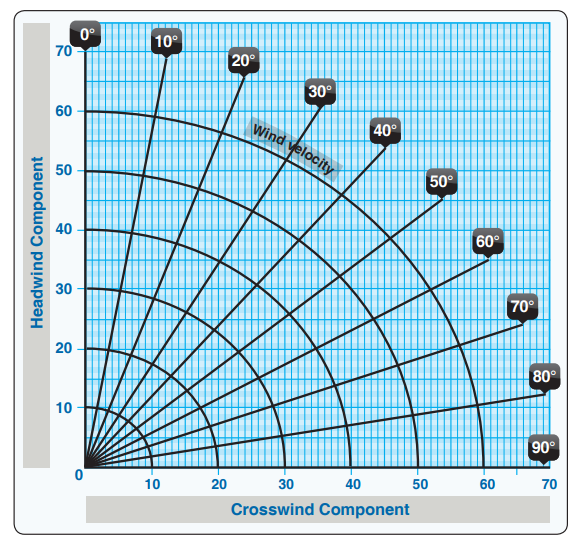

I find the 50 degree angular difference line on the crosswind chart. I follow it down past the 10 knot rainbow shaped crosswind line.

I look at where the line intersects about halfway between the 0 mark and the 10 knot crosswind line to estimate where 6 knots would be.

I determine I have about a 4 knot headwind and a 4 knot crosswind.

Now you need to consult your POH to determine how much of a crosswind your airplane can handle.

The C172 has a demonstrated crosswind component of 15 knots.

The 4 knot crosswind component I calculated is well below the 15 knot demonstrated performance in the POH so I feel very comfortable that my airplane will handle these winds.

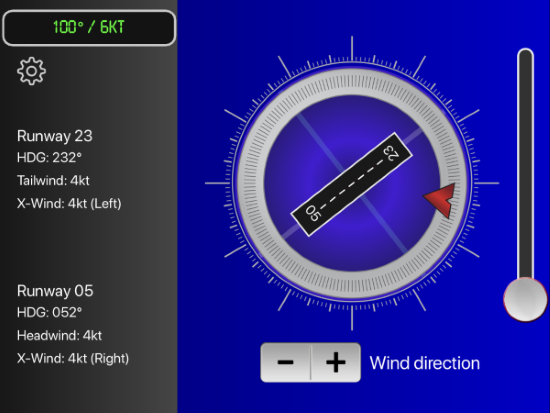

An easier way is to calculate the winds is to use an app like “Flight Winds” which will give you a breakdown such at this one:

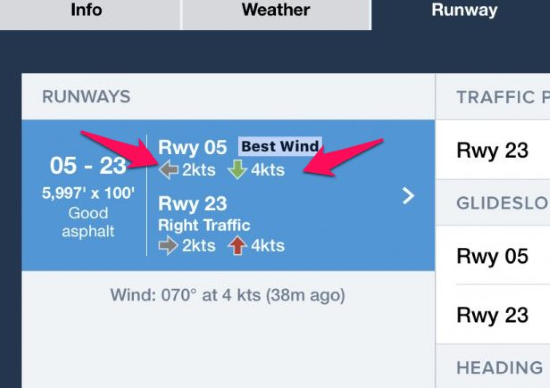

If you happen to use ForeFlight, the app will give you a breakdown of the headwind and crosswind component in real time by clicking on the runway tab:

The screen shot posted says that Grand Strand has a 2 knot crosswind and a 4 knot headwind for RWY 5, which would be a very easy landing.

Related Article – Special VFR Clearance Explained

Quick tips to help you master crosswind landings

Practice! Repetition is key. Start off with a small crosswind component and work your way up.

Follow your POH recommendations for flaps. I fly a C172 and my POH says the following:

”When landing in a strong crosswind, use the minimum flap setting required for the field length. If flap settings greater than 20 degrees are used in sideslip with full rudder deflection, some elevator oscillation may be felt at Norma approach speeds. However, this does not affect control of the airplane. Although the crab or combination method of drift correction may be used, the wing-low method gives the best control. After touchdown, hold a straight course with the steerable nose wheel and occasional braking if necessary.

The maximum allowable crosswind velocity is dependent upon pilot capability as well as aircraft limitations. With average pilot technique, direct crosswinds of 15 knots can be handled with safety.”

Also note that some POH’s will warn you against extended slips due to fuel flow concerns.

Land on the fast end of your acceptable touch down range.

The slower you are, the more vulnerable you are.

I like to come in a little bit faster on crosswind landings and will leave in a little bit of power until the last second.

Essentially “flying” the airplane down onto the runway rather than gliding it in.

Summary

Although crosswind landings can be difficult, with enough practice they will become second nature and remove the stress that comes with flying into single runway airports!

References

FAA Airplane Flying Handbook Chapter 8

FAA Airplane Flying Handbook Chapter 12

https://www.puc.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/9065/FAAH80833a-AFH-Ch7-9.pdf